"ttyymmnn" (ttyymmnn)

"ttyymmnn" (ttyymmnn)

03/13/2019 at 12:35 ē Filed to: wingspan, planes you've (probably) never heard of, Planelopnik

5

5

8

8

"ttyymmnn" (ttyymmnn)

"ttyymmnn" (ttyymmnn)

03/13/2019 at 12:35 ē Filed to: wingspan, planes you've (probably) never heard of, Planelopnik |  5 5

|  8 8 |

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

From the

Planes Youíve (Probably) Never Heard Of Department

of Wingspan, we bring you the

Curtiss XF13C.

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

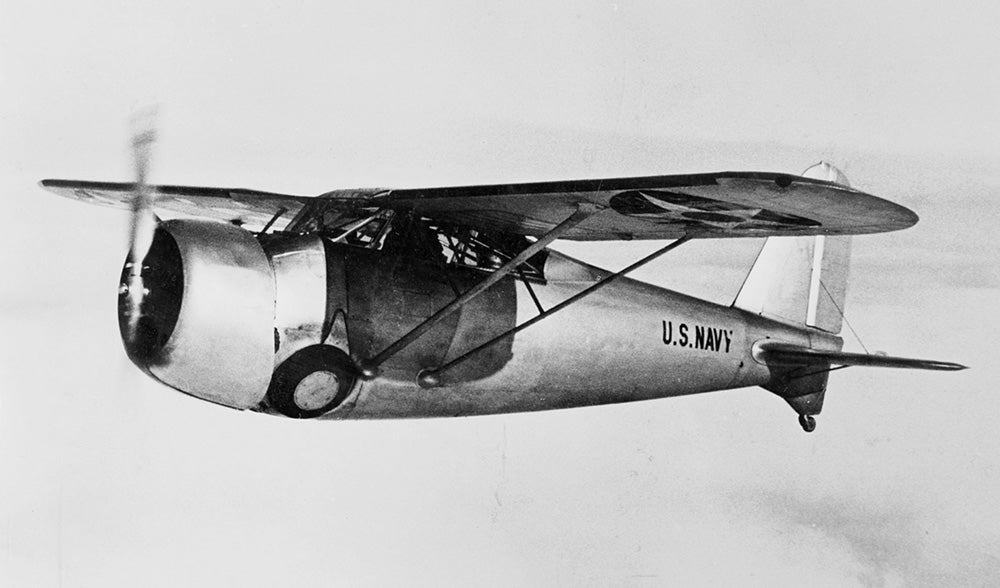

The XF13C-1 monoplane in flight in 1934 (US Navy)

The decade of the 1930s was a fascinating time of rapid aircraft development that was marked by the inexorable change from the biplane to the monoplane. Biplanes had been around since the Wright Brothers (though !!!error: Indecipherable SUB-paragraph formatting!!! famously went the monoplane route), and the two-wing arrangement does benefit from greater lift, better slow speed handling, and more maneuverability when compared to early monoplanes. For that reason, biplanes are still common today. But the monoplane, by ditching one wing and all the attendant struts and bracing wires, is an aerodynamically cleaner design, and less drag generally means more speed. With both layouts showing their own benefits (and drawbacks), it became a question of which flying characteristic was deemed more desirable in an era of transition. But what if you could have both a biplane and a monoplane in the same aircraft? Then, with a few simple steps, you could transition from one to the other. That is exactly what Curtiss attempted to do with the XF13C, known to Curtiss as the Model 70.

The XF13C-2 in its biplane configuration. The lower wings attached to the fuselage at the same points as the monoplaneís wing braces. The landing was retracted by hand. (San Diego Air and Space Museum)

At a time when the US Navy was transitioning from its last biplane fighter ( !!!error: Indecipherable SUB-paragraph formatting!!! ) to its first monoplane fighter ( !!!error: Indecipherable SUB-paragraph formatting!!! ), Americaís ocean-going force thought it might be possible to have one plane that would be the best of both worlds: a biplane, whose slower landing speeds and greater lift made it ideal for carrier duty, and a monoplane that could operate from longer land-based runways and enjoy a higher speed. So the XF13C was designed to have a removable lower wing which could be could be used or not, depending on where it would be operating. As a monoplane (XF13C-1), the permanent top wing was mounted on the top of the canopy, and its supporting struts fit into the same mounting points where the detachable lower wing would mount in the biplane configuration (XF13C-2). The only significant drawback was poor pilot visibility, since the pilotís head was squarely between the upper wings.

The Curtiss XF13C-3 fighter at the NACA Langley Reserch Center 1937. The metal bracing around the canopy served as additional support for the wing in monoplane configuration. (NASA)

The XF13C took its maiden flight on January 7, 1934 in biplane configuration and subsequent flights evaluated the monoplane configuration. As expected, the biplane had a shorter takeoff run, but the landing speed of the of the monoplane, with its leading and trailing edge slats, was only marginally faster, though its takeoff run was considerably longer. By all accounts, the aircraft was stable and had good flying characteristics, though the US Armyís evaluation of the XF13C found it wholly unsuitable for any military use. Carrier evaluations were carried out on the USS Saratoga (CV 3), where it performed acceptably.

The XF13C-2 biplane. Even though -2 was the designation for the biplane configuration, the tail number remained -1 regardless of the configuration until the arrival of the XF13C-3. (US Navy)

After testing, Curtiss took the Navyís recommendations in hand and gave the quick-change fighter heavier armament, a larger vertical stabilizer, and a more powerful experimental Wright XR-1510 engine which increased top speed slightly. Testing of the newly-dubbed XFC13-3 continued, but the engine proved problematic, and newer aircraft, even newer biplanes, were demonstrating better overall performance. In the end the innovative aircraft was passed to NACA for more testing, and it finished its days in US Marine Corps service as a utility aircraft before being retired and dismantled in 1938.

The XF13C-1 from behind, showing the greenhouse canopy, as well as the pilotís position between the upper wing (US Navy)

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

More Planes Youíve (Probably) Never Heard Of

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

For more stories about aviation, aviation history, and aviators, visit

!!!error: Indecipherable SUB-paragraph formatting!!!

. For more aircraft oddities, visit

!!!error: Indecipherable SUB-paragraph formatting!!!

.

!!! UNKNOWN CONTENT TYPE !!!

RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht

> ttyymmnn

RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht

> ttyymmnn

03/13/2019 at 12:42 |

|

Two, two, two posts in one:

#kinja

Gerry197

> ttyymmnn

Gerry197

> ttyymmnn

03/13/2019 at 12:44 |

|

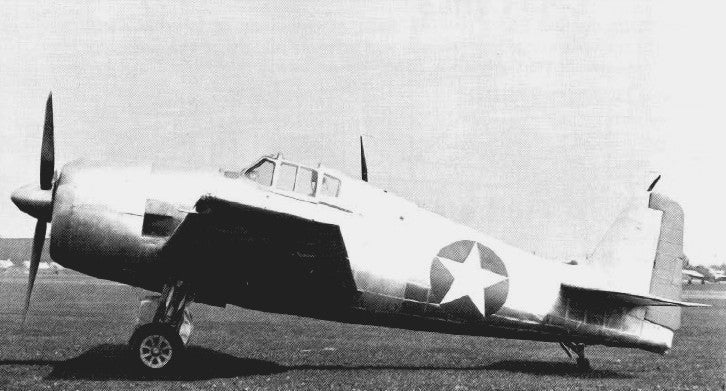

Looks a whole lot like a Wildcat F4F.††

ttyymmnn

> RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht

ttyymmnn

> RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht

03/13/2019 at 12:46 |

|

Not entirely Kinja. As I was editing the original post, a bad image caused the post to fail to save. So I created a new one and did a copy/paste. Then I forgot to delete the first one. While itís a great unintended troll, I deleted the older one.

user314

> Gerry197

user314

> Gerry197

03/13/2019 at 12:54 |

|

Yeah, thereís definitely some family resemblance there.

ttyymmnn

> Gerry197

ttyymmnn

> Gerry197

03/13/2019 at 12:56 |

|

Not surprising for that era. What is also interesting is to look at the evolution from the Grumman FF to the F6 F (the F5F was an outlier, and doesnít belong to this family) .

RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht

> ttyymmnn

RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht

> ttyymmnn

03/13/2019 at 14:02 |

|

Off-topic: I posted yesterday

a book order I made that arrived

, and RacinBob in the comments posted some pictures of a very nice classic WWII paperbacks collection.

ttyymmnn

> RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht

ttyymmnn

> RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht

03/13/2019 at 23:03 |

|

Do you have a link?

RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht

> ttyymmnn

RamblinRover Luxury-Yacht

> ttyymmnn

03/14/2019 at 09:10 |

|

https://oppositelock.kinja.com/1833250087